As a member of the WPP Open Data & AI community, I was asked to facilitate a discussion for the new series of sessions, “the Speaker’s corner”. I happily accepted the invitation, the community is very enthusiastic with loads of technical and domain expertise. However, I wasn’t sure what I should speak about. What subject should I bring to engage the audience?

Then a couple of days later I revisited the documentation of an old model. It wasn’t very detailed. I was mad at myself, I thought “this is such a bad habit of mine. I need to make better documentation”. And then it clicked, I decided to talk about good and bad habits and practices in data science. Admittedly, we all have both, so that’s a great topic for discussion and sharing our experiences.

I started making a list of points, but soon the list expanded to about 20 points. I shared my list with a couple of colleagues who added even more useful ideas. Here, I am documenting all the points from my initial list, my colleagues’ suggestions and the community’s comments and experiences shared during the session. The list is split into two sections, general practices and technical. I hope you enjoy it and find it useful.

|

|---|

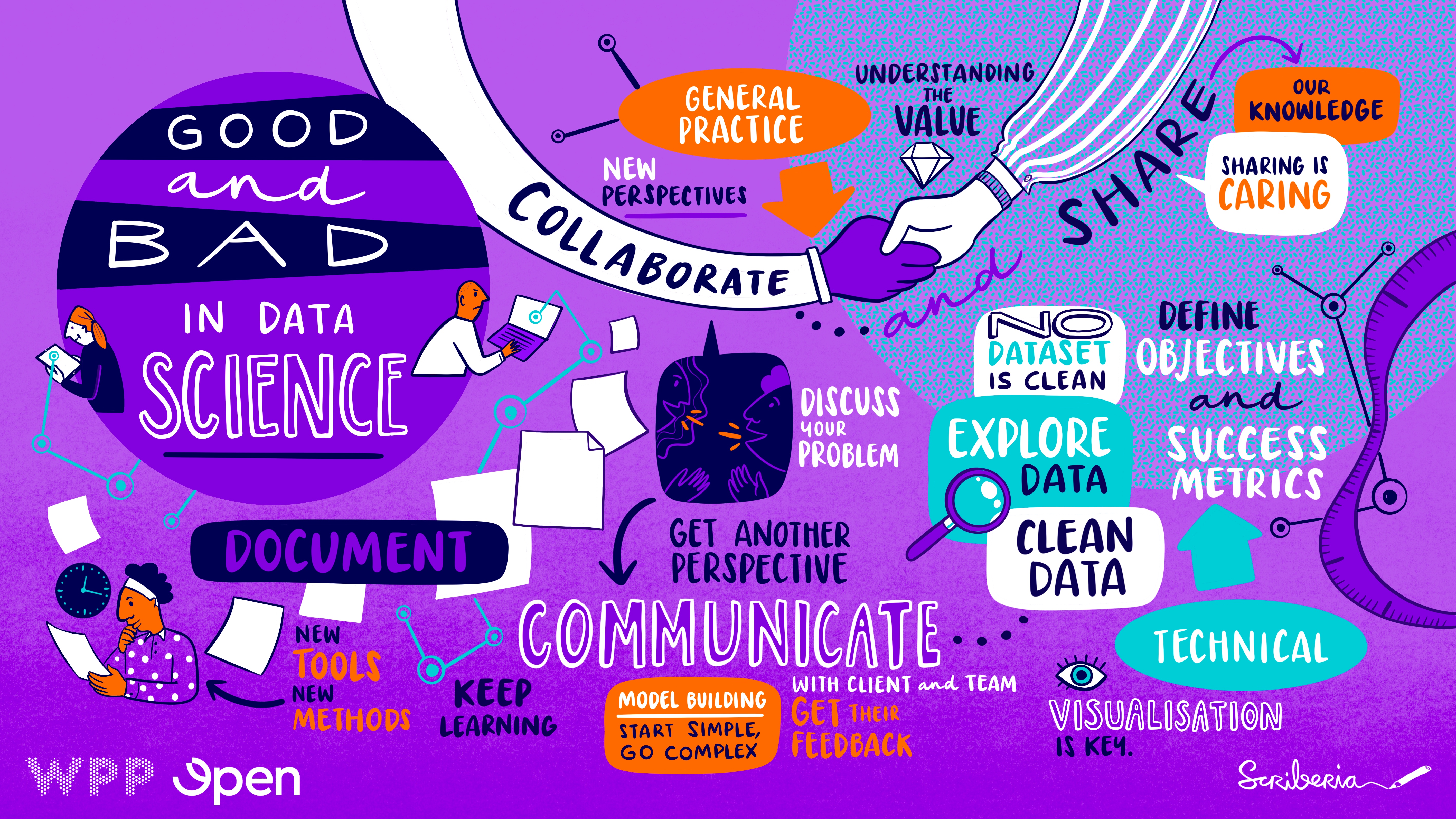

| Fig. Art-work by Scriberia summarising the key concepts of the discussion |

General Practices

- Sharing is caring. Sharing knowledge is a great habit for data science teams. Share a new tool, a new method or a new trick you learnt. This can be done in so many ways:

- Write a “how-to” article when you figure out how a tool works.

- Use tools that allow collaboration, e.g. GitHub/GitLab, Confluence, shared cloud drives

- Don’t be afraid to get exposed.

- Do not reinvent the wheel. If a colleague has done a piece of work, ask and use it.

- Similarly, be kind and share your work, the favour will be returned.

- Share beyond your team with the wider company or community (e.g. through blog updates). An interesting point was raised during the discussion about sharing sensitive client knowledge and information. This should not be overlooked and permissions should be asked before sharing sensitive information.

- Research and learn. Keep learning new techniques, develop your skills and gain domain knowledge. Data science is such a fast-paced field with new tools, novel techniques becoming available and new trends emerging every year. Being up to date with the literature and the industry is a must skill for a data scientist. This can be done in various ways:

- Follow popular blogs, e.g. Medium, Towards Data Science, KDnuggets, kaggle to name only a few among many great sources.

- Get involved to new projects and explore new areas of data science, new methods or tools.

- Take online courses on subjects of interest. There is plethora of (free and paid) courses online, Coursera is a popular such platform.

- Be surrounded by data science enthusiasts, for example your colleagues. Most likely you will hear about a new tool from them.

- Collaborate and avoid silos.

- Discuss your problem, speak out your approach, it helps identify weak points and issues.

- Get another perspective. A second or third opinion is always helpful and insightful.

- Personally, When I get stuck or uncertain I try to explain my problem to a colleague. Not only can I get their opinion, I very often find the answer just by trying to formulate the arguments out loud.

- Document your experiments, results, processes, etc., continuously.

- It helps others to understand your work and follow up on it, see for first point.

- It helps you to revisit a problem later on (been there several times!)

- If a project has a tight deadline, spend some time just after the deadline for documentation.

- Another interesting point was brought up during the session about documenting for technical and non-technical teams. This is such an important point. Successful documentation should to be read, easily understood and used as a future reference. Before writing documentation, the target audience should be identified. Here, I follow either of these two approaches. Either I write a single document which starts with the top-level information (goal, approach, results) for non-technical audiences and then go into technical details in subsequent sections or in the appendix. Second approach is to write two documents, one technical and another non-technical with cross-references between them.

- Communicate unknowns, hurdles and results with client/team regularly.

- Ask for clarifications.

- Understand the business problem behind the task rather than just doing the ask.

- Get their feedback on findings, model approach, etc.

- Organise code/files in different projects, modules, etc. If using Python, use different environments for different projects, see below. This might sound so trivial to many, but the image of individual files spread on a laptop desktop gives me nightmares. And we all know people of this kind.

Technical

-

Clearly define the objectives and deliverables. What type of model is it (e.g. classification, regression, etc.)? What are the deliverables, e.g. a report or a deployed model?

-

Make data retrieval as easy as possible. Concentrate all relevant data in a single database. Avoid multiple (Excel) files (particularly if they are scattered all over).

- Spend time to clean the data from outliers, missing values, etc. From my multiyear experience in the field I ve come to know one golden rule. No dataset is clean. Communicate with the team/client about the inconsistencies, methods for dealing outliers and missing data. My colleagues shared two fun facts

- On average 45% of time is spent on data preparation tasks, according to this survey.

- Prof Andrew Ng, an advocate for a data-centric AI, see here - ok the Video is too long, here is a 5-minute article - launched a competition where the goal was to improve the quality of the input data having a fixed model. The impact from cleaning the data can be significantly bigger than the gains from model improvements.

-

Spend time to explore your data (EDA). Any early insights/wins? Does the data make sense? Any surprising findings? Communicate findings with the team/client.

-

Define your metric of success. Different problems have different measures. There is no-size-fits-all (see accuracy). Identifying a rare disease might require more than a single metric (see ROC). Finally, validate the metric against the business ask.

-

For machine learning (ML) problems: Be aware of imbalanced data! This couples with the above point about metrics of success. Do spend time to treat imbalanced data.

-

For ML problems: Respect the train-validation-test split. Your test set is unseen data. Do not allow for training data leakage into the test set. Report model performance on the test set, not on the validation set. This is ML 101 and so trivial to many. However, after reviewing tens of papers (see our review article on low voltage load forecasting), I was surprised to see that tens of published papers have made this beginners’ mistake.

-

Model building: “Start simple, go complex”. Start with a simple model. Communicate early results with the client/team. No need to over-engineer the model from the beginning. Get feedback and add features/complexity progressively. The process of model building is never-ending. Communicate with the team/client, when is the model good enough for the purposes of the project?

- Communicate the results effectively.

- Visualisation is key. Invest time in creating a great visualisation. If it is not your strength (definitely not mine!), ask for help from a colleague.

- Know your audience. What is the target audience? Are there technical people, business or a mix? What are the objectives of the meeting? Adapt your presentation for the target audience.

- Use benchmark models. To be honest, this point is in my top five list, however, somehow I forgot to include in my initial list, even though I use benchmark models in all my models. Luckily, it was brought up during the discussion. A benchmark model is a simple baseline model, which serves as a point of reference of improvement for more complex models.

- Benchmark models are usually easy to understand and develop. For example, in load forecasting, which has strong weekly seasonality, a benchmark model could be the same value as same day and time last week, or the average of the past 3 weeks. This can be easily understood by non-technical audiences too. Comparing the improvement of the model performance of a sophisticated complex model to the benchmark can leverage

- Model interpretability. This is a debated topic. Modern deep neural network models have achieved extraordinary accuracy in vision and natural language problems, however, they lack interpretability (also known as black-box approaches). On the other hand, many business questions need to understand the why and what, e.g. what are the most important features that contribute to the model prediction? Such an understanding can inform important business decisions. Model interpretability depends on the business question at hand and it is worth discussing it with the client or team before the model building. An interpretable model might be preferred to a black box approach that improves only slightly the performance. Machine learning interpretability is a very hot field in data science.

More technical

- Reproducibility is key! Anyone must be able to reproduce your work, model, experiments, etc. Fortunately, there are a plethora of open-source tools in the community for such purposes:

- Use code revision tools, such as GitHub, GitLab, etc.

- Use virtual environments, e.g. Conda or Pipenv for Python.

- Fix random processes during experimentation if needed.

- Package your pipelines and model into docker containers.

- Scalability, optimisation and costs. The years of developing models on our local machines for experimentation and proof of concept projects are well behind us. Models are now being developed to be put into production and serve applications. When developing a model, scalability, optimisation and cloud costs should be considered upfront.

- Design scalable solutions that integrate easily with new data, tools, and clients.

- For a production solution, think of the UI, software developers and costs. Optimise the solution to fit the needs of the production.

- Write modular code or model components (i.e. create modular pipelines).

- Separate tasks in different components. E.g. Data pre-processing (outliers, missing values) should be separate from feature extraction.

- Similarly, training and validation should be separate.

- Pros: If you decide to change a hyper-parameter in the model validation you don’t need to re-run data pre-processing and/or feature extraction.

-

Develop reusable components into internal libraries for wider use and scalability.

- Code review. Set-up code-review processes. This has multiple advantages

- Ensures code quality.

- Reduces the risk of bugs in the code.

- Learning. From my experience, I learn most of tools and tricks through the code-review process (either reviewing others’ code or by suggestions when my code is reviewed).

Conclusions

The list of good and bad practices is never-ending and this article is getting into the area of a data science tutorial blog. I will stop here knowing that there are many more important points to cover. You might think that this list is lacking bad practices. Well, the absence of good practices are bad practices. Try to adopt the good practices and discard the bad ones.

Obviously, there was not much time to cover every single of these points during the session. I initiated the discussion with my top three points, which are:

- Sharing is caring

- Keep learning and researching

- No dataset is clean

PS: One thing is clear: I love lists.